Why matrix organizations will never get agile

Executive summary: The matrix organization is a remnant of the dark past, plaguing innovation and complex product development to present day. Getting rid of it now is imperative, because in the new economy it’s going to drag your business down into a sinister death.

The author coaches CxOs through agile transformations to create lively, high-impact organizations.

“After this, there is no turning back. You take the red pill—you stay in Wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes. Remember: all I’m offering is the truth. Nothing more.” – Morpheus, The Matrix

The matrix organization

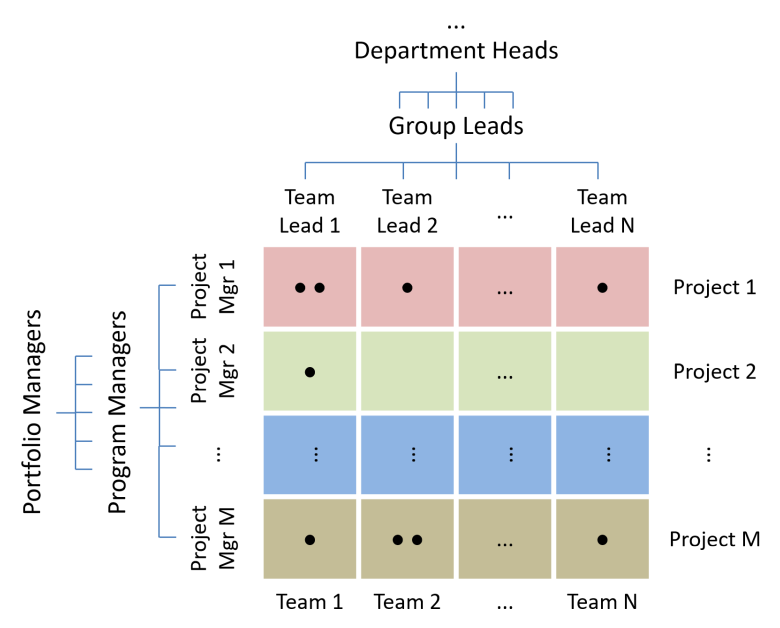

In case the misfortune of crossing paths with the matrix organizational structure avoided you, let me shortly describe the monster for you. The main idea is separating the management functions of functional and project management into two distinct sub-organizations. You do this by defining a “Line” hierarchy consisting of traditional manager roles like Team Leader, Group Leader, Department Head, etc… along job functions, and a “Project” hierarchy consisting of project roles like Project Manager, Program Manager, Portfolio Manager, etc… along the projects the organization is undertaking. The result: A highly structured, well defined organization, within which the individuals, teams and projects are all well under control. At least on the surface.

For a more detailed description and a fair analysis from around the time when the matrix went mainstream, refer to Ref. [1].

The matrix organization with functional teams and a plethora of managers

The two-headed beast is munching on delivery capability

If you call an extensive management hierarchy deadwood, double it to get a glimpse of the matrix. I used to work for a big international corporation, where 65% of all the employees were managers. I’m not joking. You couldn’t throw a stone without hitting a manager.

So why is this structure so alluring?

- Double Command and Control: Typically for hierarchies, command travels downward, workers report upward. If somebody up in the hierarchy doesn’t like what they see in the reports, divine intervention is coming (“corrective action”). You have this structure doubled, where the project hierarchy controls the projects (scope, budget, schedule, …) while line management has the control over the individuals (called “resources”) and their work (“work packages”). All these artifacts give the sense of everything being under control.

- Great career paths for management: The matrix provides great career paths and sophisticated job titles like “Senior Technical Program Manager of XY” for the ones motivated by such things.

- Power: The matrix is always an unnecessarily inflated organization. More people means (for some) more people to have power over. Herding an organization of a hundred looks impressive on your CV, even though in reality twenty could have done the job.

- Politics: If you are fascinated by company politics, the matrix is for you. The double hierarchy of management grants you a lot of opportunities to wallow neck-deep in corporate intricacies. If you are at the bottom of the hierarchies, it’s less fun though. You will have to serve a single team lead and probably multiple project leads at the same time, who are all driven by different goals. This secures that you won’t hear aligned communication on a given matter ever. Assuming they will have the time to talk to you at all.

Agile and the matrix

Even though the separation of responsibilities can help to improve agility, the way it’s done in a matrix organization is absolutely incompatible with the agile mindset. Why? Because there are…

- … no Teams: In the figure above, the spots represent individuals with delivery responsibility. They belong both to a “team” (column) and to at least one project (row). A “team” in a matrix is the set of people belonging to the same line manager and belonging to the same functional silo. As you can rarely find two individuals within a “team” working on the same project, the only thing they have to do together is to sit in the same (typically weekly) reporting meeting to report to the line manager. Since they work on different projects, this is not only boring, but also a complete waste of time.

- … no focus: In a matrix it is very common that an individual is working simultaneously on multiple projects. The context switching waste this causes is very well researched in the literature (see e.g. [2]). What this brings however, is satisfied middle management: It looks like as if everything would be proceeding in parallel — a great achievement, isn’t it? No need to prioritize and no need to be accountable for the results of the prioritization. How satisfying actual results for executives are, is another question.

- … no collocation: The people working on the same project are the ones who should collaborate closely, but location is determined by the functional teams and not by the projects. Collocation by project is anyway impossible if people are working on multiple projects.

- … no self-management: With all the different teams and projects, no two manager share the exact same goal. Heavy negotiations and political fights are behind every decision made, creating an artificially and counter-productively competitive environment that demands the full attention of managers. There’s no chance that team members can make sense of the continuous turmoil while trying to deliver, which keeps them ignorant of the larger context. They’re unable to formulate valid opinions on the direction of their own work, so they get tossed around as resource puppets by their managers who are better positioned to oversee the political landscape. You can forget about self-organization and self-management in such a hostile environment. Without self-management, you need managers. Notice how an overabundance of managers generate the need for even more managers.

- … no transparency: Everything being under control is a mirage. The organization is so complex that no human is able to have a complete understanding of the status of all the running activities. All those managers with different goals need to constantly negotiate to keep the projects above the water. In a matrix you rarely meet the managers during normal office hours: They are sitting in meetings all day long, trying to align with the others. If they also want to get stuff done, they need to take overtime and risk burning out.

All in all, agile organizations are about flexibility, quick learning and adaptation, while the matrix is about management, politics, influence and a continuous power struggle. The two pull the organization in opposite directions.

The agile matrix: Riding a dead horse [3]

The matrix organization idea is a remnant of the dark past, when organizations and consultants tried to handle increased business and product complexity by increasing the complexity of the organization itself, in order to exert more control. Some large organizations I worked with felt the need to reduce the risk of their agile transition by defining agile structures in addition to the matrix one (ever heard about the role “Scrum Master / Project Manager”?).

My opinion is rock solid on this. For the reasons detailed above, the matrix will never ever get agile. Sticking to the matrix will result in a failed transformation. If you want to limit risk, start your agile experiment on a very small scale (1–2 delivery teams plus 1 leadership team) without any trace of the matrix. After you succeed, grow this seed organically at the expense of the matrix organization. This gives you a chance to experience the full power of agility without having to jump into the unknown.

To gain momentum with leading your organization into agility, join our live online “Agile Leadership: Creating and Leading Agile Organizations” coaching program. We have created our training and coaching programs with leaders like you in mind, who are ready to take action now to explore and exploit the power of agility.

[/call_to_action]

References

- Linn C. Stuckenbruck, The matrix organization. Project Management Quarterly, 10(3), 21–33, 1979. In the PMI Learning Library on the matrix organization

- M. Weinberg, Quality Software Management, Vol. 1: Systems Thinking, Dorset House Publishing, New York, 1992

- Dakota saying: “When you discover that you are riding a dead horse, the best strategy is to dismount.”

No Comments